|

Website Index :

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Country Profile:

|

|

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The State of Sabah, Malaysia

The State of Sabah, Malaysia

|

|

|

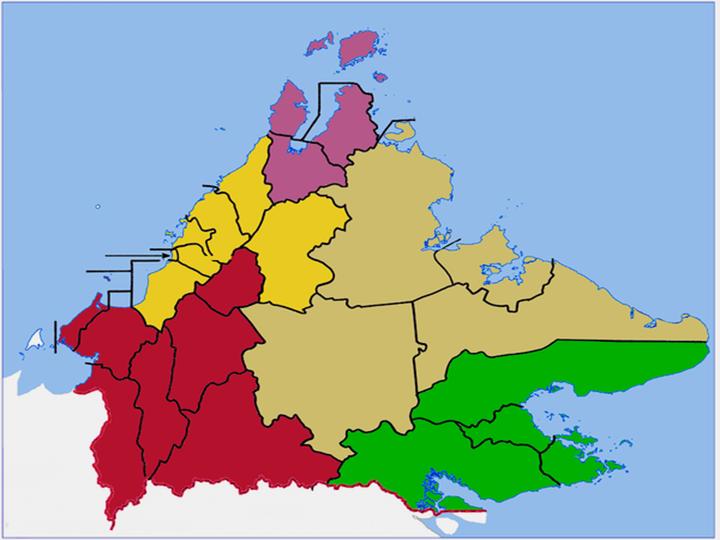

Sabah is Malaysia's eastern-most state, one of two Malaysian states on the island of Borneo. It is also one of the founding members of the Malaysian federation alongside Sarawak, Singapore (expelled in 1965) and the Federation of Malaya. Like Sarawak, this territory has an autonomous law especially in immigration which differentiates it from the rest of the Malaysian Peninsula states. It is located on the northern portion of the island of Borneo and known as the second largest state in the country after Sarawak, which it borders on its southwest. It shares a maritime border with the Federal Territory of Labuan on the west and with the Philippines to the north and northeast. The state's only international border is with the province of North Kalimantan of Indonesia in the south. The capital of Sabah is Kota Kinabalu, formerly known as Jesselton. Sabah is often referred to as the "Land Below The Wind", a phrase used by seafarers in the past to describe lands south of the typhoon belt, and it is the title of a book by Agnes Keith.

|

The Five Divisions of Sabah

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bruneian Empire and the Sulu Sultanate

During the 7th century CE, a settled community known as Vijayapura, a tributary to the Srivijaya empire, was thought to have been the earliest beneficiary to the Bruneian Empire existing around the northeast coast of Borneo. Another kingdom which suspected to have existed beginning the 9th century was P'o-ni, believed to be at the mouth of Brunei River and was the predecessor to the Sultanate of Brunei. The Sultanate of Brunei began after the ruler of Brunei embraced Islam. During the reign of the fifth sultan known as Bolkiah between 1473–1524, the Sultanate's thalassocracy extended over Sabah, Sulu Archipelago and Manila in the north, and Sarawak until Banjarmasin in the south. In 1658, the Sultan of Brunei ceded the northern and eastern portion of Borneo to the Sultan of Sulu in compensation for the latter's help in settling a civil war in the Brunei Sultanate, but many sources stated that the Brunei did not cede any parts of Sabah to the Sultanate of Sulu.

British North Borneo Company

|

North Borneo Chartered Company Board of directors 1899

|

In 1761, Alexander Dalrymple, an officer of the British East India Company, concluded an agreement with the Sultan of Sulu to allow him to set up a trading post in the Sulu area. In 1846, the island of Labuan on the west coast of Sabah was ceded to Britain by the Sultan of Brunei and in 1848 it became a British Crown Colony while the territory of Sabah ceded through an agreement in 1877, the territory on the eastern part were also ceded by the Sultanate of Sulu in 1878. Following a series of transfers, the rights to North Borneo were transferred to Alfred Dent, who in 1881 formed the British North Borneo Provisional Association Ltd (predecessor to British North Borneo Company). In the following year, the British North Borneo Company was formed and Kudat was made its capital. In 1883, the capital was moved to Sandakan and in 1885, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Germany signed the Madrid Protocol, which recognized the sovereignty of Spain in the Sulu Archipelago in return for the relinquishment of all Spanish claims over North Borneo. North Borneo became a protectorate of the United Kingdom in 1888.

Second World War and Japanese Occupation

During the Second World War, Japanese forces landed in Labuan on 1 January 1942, and continued to invade the rest of North Borneo. From 1942 to 1945, Japanese forces occupied North Borneo, along with most of the island. Bombings by the allied forces devastated most of the towns including Sandakan, which was razed to the ground. In Sandakan, there was once a brutal POW camp run by the Japanese for British and Australian POWs from North Borneo. The prisoners suffered under notoriously inhuman conditions, and Allied bombardments caused the Japanese to relocate the POW camp to Ranau, 260 km away. All the prisoners, then reduced to 2,504 in number, were forced to march the infamous Sandakan Death March. Except for six Australians, all of the prisoners died. The war ended on 10 September 1945. After the surrender, North Borneo was administered by the British Military Administration and in 1946 it became a British Crown Colony. Jesselton replaced Sandakan as the capital and the Crown continued to rule North Borneo until 1963.

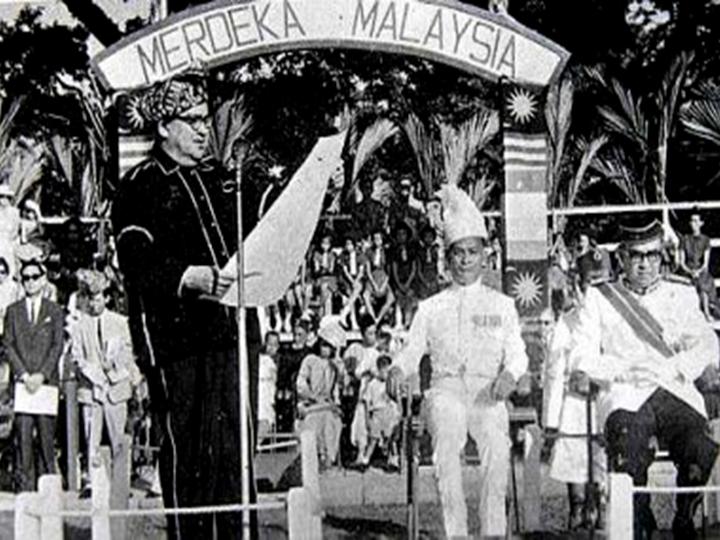

Self-government and the Federation of Malaysia 1963

|

Federation of Malaysia Declaration 1963

Tun Fuad Stephens (left) declaring the forming of the Federation of Malaysia at Padang Merdeka, Jesselton on 16 September 1963.

Together with him is the Deputy Minister of Malaya Tun Abdul Razak (right) and Tun Mustapha (second right).

|

On 31 August 1963, North Borneo attained self-government. The Cobbold Commission was set up on 1962 to determine whether the people of Sabah and Sarawak favoured the proposed union of the Federation of Malaysia, and found that the union was generally favoured by the people. Most ethnic community leaders of Sabah, namely, Tun Mustapha representing the native Muslims, Tun Fuad Stephens representing the non-Muslim natives, and Khoo Siak Chew representing the Chinese, would eventually support the union. After discussion culminating in the Malaysia Agreement and 20-point agreement, on 16 September 1963 North Borneo, renamed as Sabah, was united with Malaya, Sarawak and Singapore, to form the independent Federation of Malaysia.

Before the formation of Malaysia till 1966, Indonesia adopted a hostile policy towards the British backed Malaya, and after union to Malaysia. This undeclared war stemed from what Indonesian President Sukarno perceived as an expansion of British influence in the region and his intention to wrest control over the whole of Borneo under the Indonesian republic. Tun Fuad Stephens became the first chief minister of Sabah. The first Governor (Yang di-Pertuan Negeri) was Tun Mustapha. Between 1965 and 1967, Tan Sri Lo Su Fook became the second Chief Minister of Sabah. (He died on 1 January, 2020, in Kota Kinabalu.)

Sabah held its first state election in 1967. Until 2013, a total of 12 state elections have been held. Sabah has had 14 different chief ministers and 10 different Yang di-Pertua Negeri by 2013. On 14 June 1976 the government of Sabah signed an agreement with Petronas, the federal government-owned oil and gas company, granting it the right to extract and earn revenue from petroleum found in the territorial waters of Sabah in exchange for 5% in annual revenue as royalties.

The state government of Sabah ceded Labuan to the Malaysian federal government, and Labuan became a federal territory on 16 April 1984. In 2000, the state capital Kota Kinabalu was granted city status, making it the 6th city in Malaysia and the first city in the state. Also in the same year, Kinabalu National Park was officially designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, making it the first site in the country to be given such designation. In 2002, the International Court of Justice ruled that the islands of Sipadan and Ligitan, claimed by Indonesia, as part of Sabah.

|

|

|

|

Population

Population in North Borneo (now Sabah and Labuan) (1960 Census):

Population Percent

Kadazan-Dusun 32%

Murut 4.9%

Bajau 13.1%

Malay 0.4%

Other Muslim groups 15.8%

Indonesians 5.5%

Filipinos 1.6%

Chinese 23%

Sabah’s population numbered 651,304 in 1970 and grew to 929,299 a decade later. But in the two decades following 1980, the state’s population rose significantly by a staggering 1.5 million people, reaching 2,468,246 by 2000. By 2010, this number had grown to 3,117,405, with foreigners making up 27% of the total The population of Sabah was 3,117,405 in 2010, an increase of more than 400 percent since 1970. Sabah became the third most populous state in Malaysia after Selangor and Johor.

Sabah has one of the highest population growth rates in the country as a result of legal and purportedly state-sponsored illegal immigration and naturalization from elsewhere in Malaysia, Indonesia and particularly from the Muslim-dominated southern provinces of the Philippines who were awarded Malay stock and granted citizenship. As a result, the Sabahans, most of whom are non-Muslim, have become minorities in their own homeland and this problem has become the main cause of ethnic tension in Sabah. On 1 June 2012, Prime Minister Najib Razak of Malaysia announced that the federal government had agreed to set up a Royal Commission of Inquiry to investigate the problem of illegal immigrants in Sabah . The report findings stated that Project IC existed.

Population in Sabah (2010 Census)

Population Percent

Kadazan-Dusun 17.82%

Murut 3.22%

Bajau 14%

Malay 5.71%

Other 20.56%

Chinese; 9.11%

Other non-bumiputra 1.5%

Non-Malaysian citizen (Filipino, Indonesian) 27.81% (867,190)

Kadazan-Dusun: 17.82% (555,647)

Bajau: 14% (436,672)

Malay (Bruneian Malays, Kedayan, Banjar, Cocos and also include Peninsular Malays):(178,029)

Murut: 3.22% (100,631)

Other bumiputra: 20.56% (640,964) – which consists of Rungus, Iranun, Bisaya, Tatana, Lun Bawang/Lun Dayeh, Tindal, Tobilung, Kimaragang, Suluk, Ubian, Tagal, Timogun, Nabay, Orang Sungai, Makiang, Minokok, Mangka’ak, Lobu, Bonggi, Tidong, Bugis, Ida’an (Idahan), Begahak, Kagayan, Talantang, Tinagas, Banjar, Gana, Kuijau, Tombonuo, Dumpas, Peluan, Baukan, Sino, Jawa

Chinese (majority Hakka): 9.11% (284,049)

Other non-bumiputra: 1.5% (47,052)

Language and ethnicity

Malay is the official national language in Sabah. In addition, indigenous languages such as Kadazan, Dusun, Bajau, Brunei, Murut and Suluk are used, even in radio broadcasts.

English remains an active second language, with its use allowed for some official purposes under the National Language Act of 1967. As there are quite significant population of ethnic Chinese Sabahans, and with many Bumiputera Sabahans sending their children to Chinese vernacular schools, Mandarin is also widely used in Sabah. Spanish based creole, Zamboangueño, a dialect of Chavacano, has spread into one village in Semporna from the southern Philippines.

The people of Sabah are divided into 32 officially recognised ethnic groups, in which 28 are recognized as Bumiputra, or indigenous people. The largest non-bumiputra ethnic group is the Chinese (13.2%). The predominant Chinese dialect group in Sabah is Hakka, followed by Cantonese and Hokkien. Most Chinese people in Sabah are concentrated in the major cities and towns, namely Kota Kinabalu, Sandakan and Tawau. The largest indigenous ethnic group is Kadazan-Dusun, followed by Bajau, and Murut. There is a much smaller proportion of Indians and other South Asians in Sabah compared to other parts of Malaysia. Collectively, all persons coming from Sabah are known as Sabahans and identify themselves as such.

Ethnic Groups:

Kadazan-Dusun

Bajau

Malay (Bruneian Malays, Kedayan, Banjar and Cocos)

Murut

Rungus

Bisaya

Lotud

Kwijau

Tambanuo

Orang Sungai

Dumpas

Mangka'ak

Tidong

Maragang

Ida'an

Minokok

Rumanau

Paitan

Lun Bawang/Lun Dayeh

Illanun

Suluk

Chinese Sabahan (Sino - including mixed ancestry with the natives)

Other inhabitants:

West Malaysian : Malay, Chinese, Indian

Chinese Sabahan: Hakka, Cantonese, Teochew, Hainanese

Filipino: Chavacano, Visayan, Ilocano, Badjao, Iranun, Tausug/Suluk, Tagalog

Indonesian: Bugis, Javanese, Ambonese, Banjarese, Torajan, Chinese Indonesian

Indian: Punjabi, Tamil

Sarawakian: Iban, Penan, Dayak, Orang Ulu, Sarawakian Malay, Sarawakian Chinese

Pakistani: Pashtun

Arab people: Hadhrami

Eurasian

Timorese

Japanese

Koreans

|

|

Religion

Since independence in 1963, Sabah has undergone a significant change in its religious composition, particularly in the percentage of its population professing Islam. In 1960, there were 37.9% Muslims, 16.6% Christians, and about one-third animist. In 2010, the percentage of Muslims had increased to 65.4%, while people professing Christianity grew to 26.6% and Buddhism stayed at 6.1%.

Religion in North Borneo (now Sabah and Labuan) (1960 Census)

Religion Percent

Islam 37.9%

Animism 33.3%

Christianity 16.6%

Other 12.2%

In 1973, USNO amended the Sabah Constitution to make Islam the religion of the State of Sabah. USIA vigorously promote conversion of Sabahan natives to Islam by offering rewards and office positions, and also through migration of Muslim immigrants from the Philippines and Indonesia. Expulsion of Christian missionaries from the state was also performed to reduce Christian proselytisation of Sabahan natives. Filipino Muslims and other Muslim immigrants from Indonesia and Pakistan were brought into the state with instruction from the USNO chief, Tun Mustapha, and were given identity cards in the early 1990s to help topple the PBS state government and to make him appointed as the state governor. However his plan to become the state governor was unsuccessful.

These policies continued when Sabah was under the BERJAYA's administration headed by Datuk Harris, in which he openly exhorted to Muslims of the need to have a Muslim majority, to control the Christian Kadazans (without the help of the Chinese minority).

Religions in Sabah (2010 Census):

Religion Percent

Islam 65.4%

Christianity 26.6%

Buddhism 6.1%

Other 1.6%

No religion 0.3%

In 2010 the religion distribution of the total population of Sabah was as follows:

2,096,153 Muslim

853,726 Christian

194,428 Buddhist

3,037 Hindu

2,495 Confucianism/Taoism

3,467 followers of other religions

9,850 non-religious

43,586 unknown religion

The population distribution by religion in Sabah for Malaysian citizens in 2010 was as follows:

1,343,210 Muslim - 58%

730,202 Christian - 32%

192,881 Buddhist - 8%

2,479 Hindu - 0.1%

2,426 Confucianism/Taoism - 0.1%

2,320 followers of other religions - 0.1%

8,559 non-religious - 0.3%

34,886 unknown religion - 1.4%

The huge number of non-Malaysian Muslim citizens residing in Sabah, and also based on some of the findings from Royal Commission of Inquiry on illegal immigrants in Sabah, has led to the conclusion that Sabah had gone through a systematic granting of citizenship to foreigners to ensure favourable demographic pattern to the ruling government, in an operation named Project IC.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sandakan, Sabah: Sandakan, Sabah:

- Located on the east coast of Sabah, Sandakan is the jumping off point for eco-tourism destinations such as the Sepilok Orang Utan Sanctuary and the Gomantong Cave. Sandakan is also infamous for the Death Marches of Allied Prisoners of War from Sandakan to Ranau during the Japanese Occupation, 1942-45.

|

|

St. Michael's Secondary School, Sandakan, Sabah: St. Michael's Secondary School, Sandakan, Sabah:

|

World War II: World War II:

- The story is one of woman's confinement in a WW II Japanese prison camp.

This is a true story of Agnes Newton Keith's imprisonment in several Japanese prisoner-of-war camps from 1941 to the end of WWII. Separated from her husband and with a young son to care for she has many difficulties to face./font>

|

|

|

|